“Because the night belongs to lovers, because the night belongs to us.”

By admin | November 7, 2012

In KINO – German Film No:95 begann Ron Holloways Bericht zur Berlinale 2009 wie folgt:

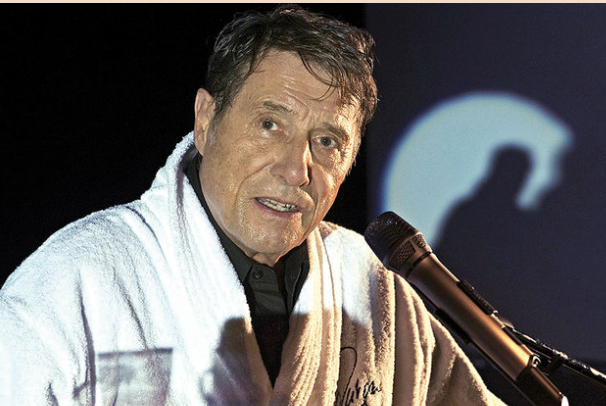

Asked whether the Berlinale has fostered an image as a “political” film festival, Christoph Schlingensief, the German jury member at the 59th Berlin International Film Festival (5-15 February 2009), stated frankly: “A competition entry here scarcely stands a chance otherwise.” Schlingensief, a highly motivated political filmmaker in his own right, hit the nail right on the head. You only have to look back at the past Golden Bear winners. In 2007, the Grand Prix went to Wang Quan’an’s fiction-documentary Tu ya de hun shi (Tuya’s Marriage) (China). Set in rural Mongolia, Tuya’s Marriage mirrored the plight of nomadic shepherds whose way of life is threatened by the government’s misguided plans to move them to urban shelters.

Am 3. November 2012 gab es zur Eröffnung des Christoph Schlingensief Archivs in der Akademie der Künste am Hanseatenweg einen Abend für Christoph Schlingensief. Freunde von Christoph trafen sich, – unter ihnen Wim Wenders, Volker Schloendorff, Patti Smith – um des Schöpfers von Filmen, Texten, Ideen und seiner so leidenschaftlichen Entwürfen zu gedenken. Sicher wäre Ron auch dabei gewesen. Die Akademie war knallvoll. Martin Eder las aus Ich weiß, ich war’s von Christoph Schlingensief, herausgegeben von Aino Laberenz. Wir sahen u. a. die Filme – oder Ausschnitte aus – Menu Total und Egomania und auf Monitoren gab es u. a. Christoph Schlingensief – Die Piloten von Cordula Kablitz-Post und von Frieder Schlaich den Interviewfilm Christoph Schlingensief und seine Filme.

Patti Smith beschenkte uns mit dem Lied: “Because the night belongs to lovers, because the night belongs to us.” Anschließend sangen wir das Lied alle gemeinsam – für Christoph und für Ron.

P.S: Wie Christoph Schlingensief hatte auch Ron Holloway noch Werke in Arbeit, die er nicht mehr vollenden konnte. Siehe KINO – German Film No: 93, Seite 34 – Alexei Gherman – Documentary Work-in-Progress by Ron Holloway. Gherman hatte das Material bereits gesehen und hatte sein O.K. gegeben. Raissa Fomina wollte mit den Rechten helfen.

Auch ein Buch über Cannes war in Planung.

Topics: German Film, International Reports, Misc. | Comments Off on “Because the night belongs to lovers, because the night belongs to us.”

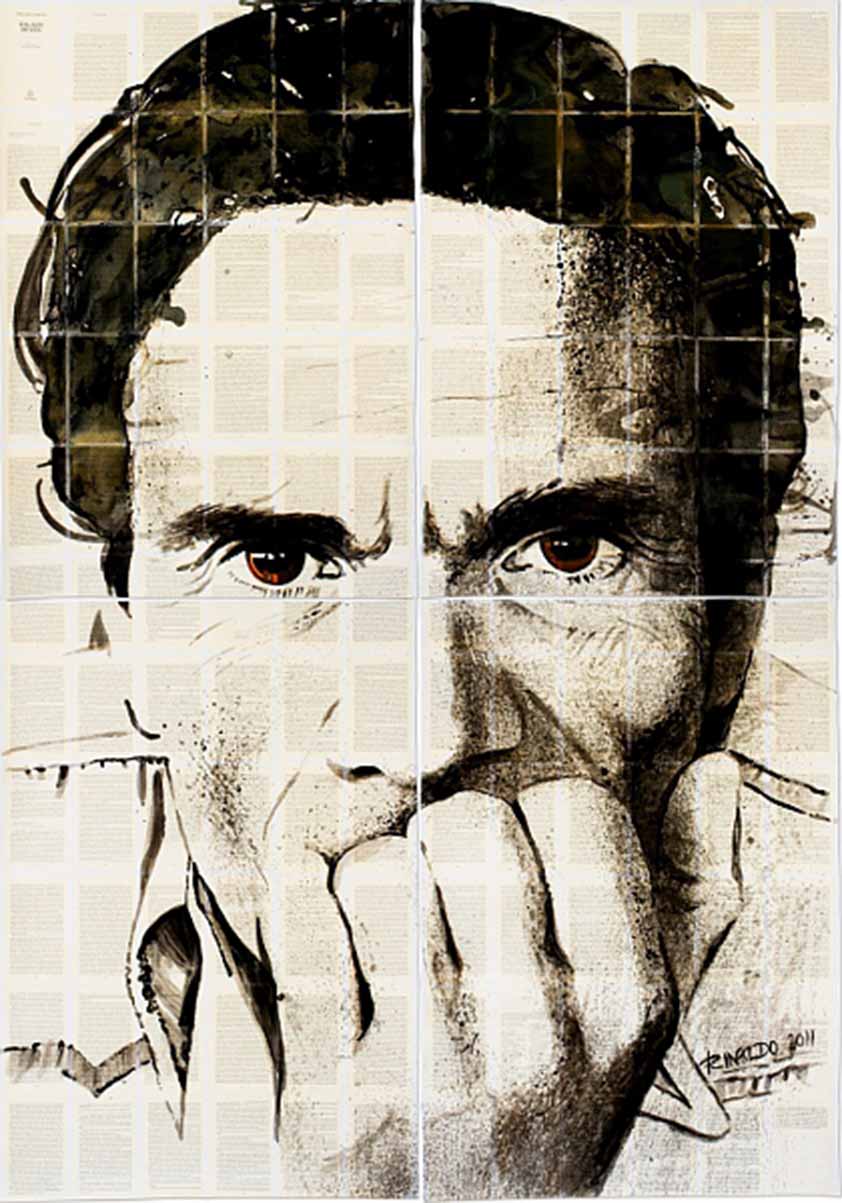

Pier Paolo Pasolini & Harry Raymon Exhibitions

By Fumiko Matsuyama | November 6, 2012

Recently, Berlin’s Schwule Museum(Gay Museum) presented two exhibitions about two gay filmmakers on display. One is the internationally famous Italian film director, poet and writer, Pier Paolo Pasolini; the other, Harry Raymon, did not go beyond the border so much, that surprises us still more.

In celebration of Pasolini’s 90th birthday his works are on view. Hanging on the wall in the entrance hall are large stills from his works, like Accattone, Teorema (Theorem), Medea with Maria Callas, and I Racconti di Canterbury (The Canterbury Tales). At the side of these photos are 36 quotations about Pasolini from such personalities as Roland Barthes and Ingeborg Bachmann to Jean-Luc Godard. This suggests that he aroused the interest of the world’s intellectuals beyond the movies. His early tragic death at age 53 – he was murdered by a teenage-boy in 1975– shocked the world at that time. It was provocative like his many films. Copies of the newspapers with the picture of his dead body are pasted on the pillar in the same room. Other stills and work photos as well as private photos in smaller sizes are in the back showrooms. Some photos remind us that Pasolini wrote screenplays for other directors: La donna del fiume (The River Girl, 1955) by Mario Soldati, La notte brava (The Big Night, aka Bad Girls Don’t Cry, 1959) by Mauro Bolognini, La lunga notte del ’43 (Long Night in 1943, 1960) by Florestano Vancini, etc. As a matter of course, his own words and books are not lacking. The display is small-scale, however essential.

Topics: German Film, International Reports, Misc. | Comments Off on Pier Paolo Pasolini & Harry Raymon Exhibitions

Sacharow-Preis an Filmemacher Jafar Panahi

By Dorothea Holloway | November 5, 2012

Die Preisträger des Sacharow-Preises für die Freiheit des Geistes des EU Parlaments kommen in diesem Jahr aus dem Iran. Es sind die Anwältin Nasrin Sotudeh und der Filmemacher Jafar Panahi.

In KINO – German Film No: 100 (2011) beginnt der Bericht über die Berlinale 61 so:

An opening with political gravitas. Before he introduced the International Jury, Dieter Kosslick brought an empty chair on to the stage with a sign bearing the name of Jafar Panahi. The Iranian filmmaker, whose Offside was shown at the Berlinale in 2006 when it was awarded a Silver Bear, had been invited as a member of Jury, but was not allowed to leave his country. The chair remained empty until the end of the festival. The work of the »Filmmaker of the World« was present in the festival’s programme with his films being shown in the Berlinale’s various sections each day. Isabella Rossellini, president of the jury, read out loud an open letter from Jafar Panahi where the artist wrote, among other things: »The world of a filmmaker is marked by the interplay between reality and dreams. The filmmaker uses reality as his inspiration, paints it with the colour of his imagination, and creates a film that is a projection of his hopes and dreams.«

And in KINO – German Film No. 101 about Cannes 64 (2011):

Directors who couldn’t come to Cannes

In December 2010, Jafar Panahi was sentenced to six years in prison and banned from making films for 20 years. He can move freely until judgement is passed by the court of appeal. His colleague Mojtaba Mirtahmasb shot a video diary with the title This Is Not A Film. He observes Panahi in his flat, shows his everyday life: a discussion with art students, a telephone call with his woman lawyer. Panahi talks about a film he was planning before he was sentenced. We see excerpts from Panahi’s films and the director speaks about his work with actors. In 2006, Ron Holloway wrote in KINO 86 about Panahi’s comedy Offside which won a Silver Bear at the Berlinale.

Meanwhile, Mohammad Rasoulof’s wife accepted the Prize for Best Direction in the sidebar Un Certain Regard for Good Bye (Be omid e didar) which was the opening film at this year’s Filmfest Hamburg. Like Panahi, Rasoulof has been sentenced to a prison sentence and a 20 year ban on making films, giving interviews and travelling abroad. Good Bye is quiet, low key, and thus all the more convincing. A woman lawyer, Leyla Zareh, goes from one authority to another, including unofficial ones, to apply for an exit visa. Her husband, a journalist, has gone into hiding. The police had already been in the flat looking for incriminating documents. The offices are grey, and Leyla’s face is also ashen. As in Asghar Farhadi’s Berlinale winner Nader and Simin. A Separation, this film is about staying or leaving. It says something about brotherliness among people that these films from Iran were both shown in Cannes. Asghar Farhadi is living now with his family in Berlin by inivitation of the DAAD. He is working on a new movie that plays in Europe. All the best for you!

Jafar Panahi’s and Mohammed Rasoulef’s sentences have been recently confirmed by an Iranian court.

Ron wrote in his Berlinale 2006 report in KINO – German Film No. 86 about Jafar Panahi’s comedy Offside:

Awarded the other half of the runnerup Grand Jury Prize, Jafar Panahi’s comedy Offside (Iran) prompted howls of laughter from a delighted audience. The scene is a soccer game at the overcrowded Azadi Stadium in Tehran, where Iran is battling Bahrain in a key match to qualify for the World Cup this summer in Germany. Here, six plucky Iranian girls, all but one rabid soccer fans, are using their wits and helpful disguises to enter the stadium as boys with caps, garb, pennants, and painted faces. One even dons a soldier’s uniform, an indiscretion that could easily lead to family disgrace and a jail sentence. The girls never get to see the game – instead, they are caught and placed »offside« in a pen under the guard of a friendly soldier who wants to watch the game as badly as they do. The rest is an ongoing dialogue between the girls and the guards about why women are forbidden to enter a soccer stadium in the first place. To Jafar Panahi’s credit, each of the non actors is a windfall to this amusing tale on nonsequiturs as it unfolds. For, as Jafar Panahi has so aptly demonstrated in past films, particularly in The White Balloon (1995), illogical answers to logical questions can bring tears of laughter.

Some weeks later the Berlinale staff can congratulate: »1:0 for Iranian Women. Women once again have access to Iranian football sta-diums. On this occasion, the Berlin Internation-al Film Festival would like to congratulate the Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, who tackles the theme of unequal treatment of women in his film Offside, awarded the Silver Bear – Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Berlinale.« (Press Office, 28 April 2006)

Laut berliner Tagesspiegel vom 28. Oktober 2012 reisen EU-Parlamentarier nicht nach Teheran, da sie die Preisträger dort nicht treffen dürfen.

I was at the 7th Isfahan International Festival of Films for Children and Young Adults 6 – 12 October 1991 im Iran. I wrote about in KINO – German Film No: 44 (1991) more than 2 pages. Here are some sentences from my Isfahan-Report:

The trip to Iran was rewarding in more ways than one. For not only was there the competition entries at the festival to view each afternoon, and this in an historical city of breathtaking architectural beauty, but one also had the opportunity to spend hours talking with Iranian filmmakers and journalists, as well as viewing on cassette or at the retrospective a collection of some 60 films produced in Iran since 1985 – from the fascinating and strikingly photographed Runner (1985) by Amir Naderi to the latest productions of 1991. Festival director Ali R. Shoja Noori and his friendly team announced a policy of “standing by for 24 hours” in the video room of the Abbasi Hotel to be at the service of foreign guests.

Topics: Film Reviews, International Reports | Comments Off on Sacharow-Preis an Filmemacher Jafar Panahi

Ziegler Retrospektive

By Dorothea Holloway | October 26, 2012

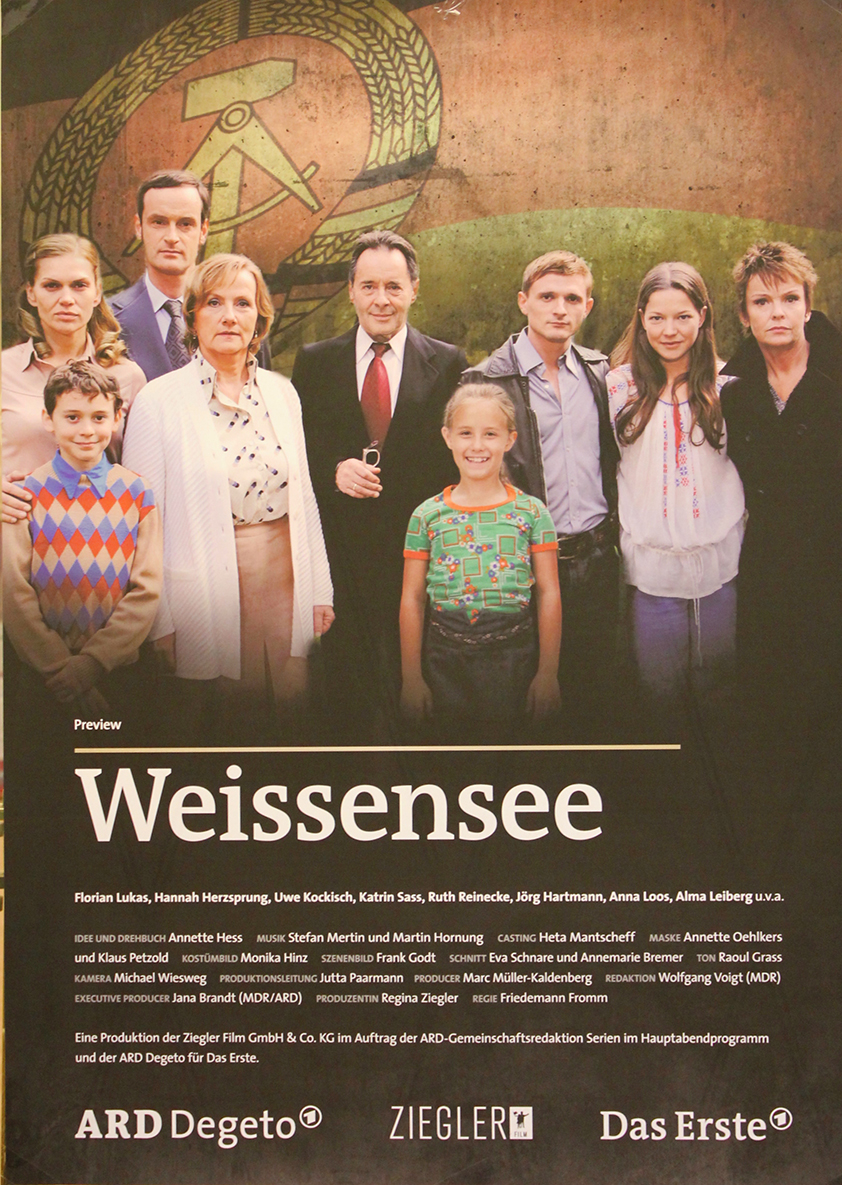

»The Weissensee ensemble is simply magnificent – and each episode a magic moment.« Courtesy Ziegler Film for ARD Degeto/Das Erste

Am Mitwoch den 24. Oktober 2012 wurde in Berlin in einer Lichtung im Tiergarten, nicht weit vom Brandenburger Tor und dem Reichstag, das Mahnmal für die ermordeten Sinti und Roma eingeweiht.

Wenn ich jetzt über Regina Ziegler berichte, so gehört dazu, dass Regina Ziegler 1990 den Feature Film Korczak von Andrzej Wajda produzierte in Co-Produktion mit polnischeb, französischen und britischen Partnern. Zitat Ron Holloway in KINO – German Film No: 38, 1990 in his Cannes Report:

“In view of the fact that it took Wajda more than a decade to bring to the screen his story of Dr. Janusz Korczak, the famous Warsaw pedagogue who went with the Jewish children under his care into the gas chambers at Treblinka, one has to add that the production was only made possible via West Berlin coproducer Regina Ziegler.”

Am 27. Oktober wird Professor Regina Ziegler in Berlin mit dem PRIX EUROPA LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD 2012 ausgezeichnet:

To mark the presentation of the price Filmkunst 66 is staging a retrospective featuring a selection of some of her wonderful films. Zitat about Korczak in the program of Filmkunst 66:

“Korczak is intended as a tribute to a man who spent a large part of his life following an ideal.”

Die Ziegler Retrospektive wird eine Vorführung von Weissensee (Folgen 1-6) am Samstag, den 27. Oktober um 17 Uhr im filmkunst 66 abschließen. Produzentin Prof. Regina Ziegler, Regisseur Friedemann Fromm, Drehbuchautorin Annette Hess und Producer Marc Müller-Kaldenberg erzählen über die Produktion dieser mit dem Deutschen Fernsehpreis 2011 ausgezeichneten erfolgreichen ARD-Serie und beantworten die Fragen des interessierten Publikums.

www.ziegler-film.de

www. filmkunst66.de

www.prix-europa.de

Topics: German Film, International Reports | Comments Off on Ziegler Retrospektive

Werner Herzog im Arsenal

By Dorothea Holloway | October 24, 2012

“Werner Herzog is one of those directors who appears to have been born only to make films; …” wrote Ron Holloway in 1983 in KINO – German Film No: 12.

Mit wie grosser Freude hätte Ron nun im Arsenal die Dokumentarfilme des begnadeten Autorenfilmers Herzog angeschaut. Am Sonntag (21.10.) lief Death Row. Portraits: James Barnes, Hank Skinner. Das Arsenal war bis auf den letzten Platz ausverkauft; das Publikum betroffen, ergriffen und stellte kluge Fragen, die Werner Herzog wahrhaftig, schnörkellos, offen und manches Mal auch mit Humor beantwortete. Herzog: “Ich spreche nicht mit Männern, denen schwere Verbrechen vorgeworfen werden, ich spreche mit Menschen.”

Bei der Berlinale lief Death Row in Berlinale Special. Siehe: KINO – German Film No:103, 2012 – Seite 14.

Topics: German Film | Comments Off on Werner Herzog im Arsenal

Glückwunsch Regina Ziegler und Team!

By Dorothea Holloway | October 22, 2012

Für Der Mann mit dem Fagott (The Man with the Bassoon) bekam Ziegler-Film in der Kategorie Serie den Deutschen Fernsehpreis 2012.

In KINO – German Film No: 102, Seite 45 habe ich darüber berichtet mit Bild (!) habe aber nicht gesagt Produktion Ziegler Film!

The Man with the Bassoon has two parts, therefor the price in the section Serie.

Topics: Misc. | Comments Off on Glückwunsch Regina Ziegler und Team!

Red Sorghum – Golden Bear at the 1988 Berlinale

By Dorothea Holloway | October 18, 2012

Mo Yan, author of the novel Red Sorghum, will be awarded this year’s Nobel Price for Literature. In 1988 Zhang Yimou won the Golden Bear for his screen adaption of Mo Yan’s work. To honor the Nobel Price Commitee’s decision here my review of Zhang Yimous award-winning film:

The images in Red Sorghum overwhelm. The eyes are stunned and wrenched by imagery that fairly burst the borders of the frame. A strange and foreign world is unveiled.

All the more impressive, this is a debut film – although its director, Zhang Yimou, was already known as the cameraman for Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth (1984) and The Big Parade (1985), both of which have made the rounds of international festivals to introduce the film world to a still relatively unknown land of myth and magic.

This Chinese entry at the 38th Berlinale, winner of the Golden Bear, impresses, first of all, for its color-composed narrative style – consequent from beginning to end, applied without compromise, as rare in its demands upon the viewing audience as it is fascinating in its conceptual breadth. When the red sorghum field sways from one side of the frame to the other, the effect of being drawn along with the images is breathtaking. Yet this stylistic factor does not impose any extra weight upon the thematic content. Rather, it underscores the film’s dramatic depth as a film-ballad, a ballad about the passion of a woman in China of the troublesome 1920s and 1930s.

Red Sorghum opens with waves of the cornfield in the wind. We find ourselves in the midst of a red ocean of shoulder-high grain, and through it a bride is being borne in a red hand-carriage on the shoulders of bearers in her entourage. As is customary for a wedding, she is clothed completely in red, down to a red veil covering her face. Her father has sold her to an aged gin-distiller. To make things worse, her journey is anything but a pleasure: the constant to-and-fro movement of the bearers is more than enough to make her ill. The entourage makes fun of the whole affair: the accompanying musicians sing and dance, as do the bearers themselves as they tote the carriage. Suddenly, everything grounds to a halt, and the merrymaking stops – inside, the weeping of the suffering bride can be heard.

Then a bandit emerges from the sorghum field: he intends to kidnap the bride. But Yu, one of the bearers and as strong as a bear, beats off the attacker – and kills him. The entourage continues on its way. Upon arriving at the gin-distiller’s manor – house, the bride is left to sleep in the courtyard, rather than the manor itself – for her future husband has leprosy. Here again the images are striking: a night bathed in blue, crowned by a full moon.

After three days, according to custom, the bride returns home to the house of her father. This time, however, she’s riding on the back of a donkey.

Again, the way leads through the sorghum field – and, again, she is set upon by attackers. A masked abductor carries her off into the red field. It is Yu, the carriage-bearer who saved her honor at the outset of the trip. He has prepared a bridal-chamber on a bed of red cornstalks. They make love, and a son is begotten.

Sorghum supplies the film’s central motif. It is planted in China for the grain it bears. Eaten, the cereal nourishes like rice; brewed, the red liquid jolts the senses like potent gin. The images are now those of blood and death, of violence – unexpected, genuine, unusual, overpowering, without respite. The gin is brewed in jugs that can contain a full-grown man, and we see how it is made by barechested men bathed in sweat. The ritual is experienced in documentary detail, although the scene is not blown out of proportion for the sake of effect. Each worker receives his share of the brew for drinking, for singing, even for praying. The gin flows – like blood from an open wound.

Now the Japanese invaders have arrived. The son of the couple is 9-years-old. The villagers are forced by Japanese soldiers to trample down the field of red grain with their bare feet; a roadway has to be constructed. As a lesson to resisters, the foreman of the gin-mill is skinned alive as an example to terrorize the villagers into submission. He has refused to cooperate with the Japanese. Later, the Chinese take their revenge: the road is mined – and when the Japanese return the fire, an explosion leaves behind a gaping crater. Nearly everyone dies in the blood-bath, save for the boy and his father. The sun sets – a flaming red ball.

More than just a film set against the fiery background of a field of red grain, Red Sorghum weaves the myth and magic in its rich imagery of a “Deutscher Wald” in its deeply profound sense. This is a place of dark secrets. The heads of grain waving in the wind impose the same artistic density as the mysterious shadows of a forest. The sorghum field can shelter bandits and hint of ghosts. It can provide a fitting veil for love-making and serve as a bridal-chamber. It can cradle life and be reduced to a wasteland of death and destruction.

Red Sorghum – a signal, too, of the advent of contemporary Chinese cinema on the world film scene.

Topics: Film Reviews, International Reports | Comments Off on Red Sorghum – Golden Bear at the 1988 Berlinale

Barbara by Christian Petzold

By Doreen Butze | September 24, 2012

Barbara ist the new movie directed by Christian Petzold. It’s his third movie after Gespenster (2005) and Yella (2007) and also his Competition entry at this year’s Berlinale – and it now is Germany’s entry for the Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award for 2013.

At the beginning of the 1980s in East-Germany: the talented doctor Barbara (Nina Hoss with a great, restrained performance) gets banished from Berlin after trying to get an travel visa. Barbara finds herself in a small northern GDR town. She works in a local hospital there. Her new boss André (Roland Zehrfeld) cares about her, but she is cold and tries to keep distance. She confides in nobody. Subject to a constant observation by a unpleasant Stasi officer (Rainer Bock) she is being even unable to take a step outside the door for riding her bicycle or going for a walk privately.

Actually she is planning together with her West-German lover Jörg (Mark Waschke) her escape from the GDR across the Baltic Sea.

After a while all her rejections turn slowly into a slight sympathy for chief physician André, whose real intentions are never quite clear. The bonds were intensified once again as the young and rebellious girl Stella (Jasna Fritzi Bauer) came into the clinic. Barbara has to make a decision …

Petzold’s film doesn’t give a blanket judgment about the GDR. The director goes more to the micro level of social relations and tells us a nuanced conflict in decision making. Barbara’s dilemma: On one side stands the life of freedom in West Germany with her beloved Jörg. On the other hand, there is the lovefor the profession and the people who need her aid.

The complexity of the characters is a strength of the film. A telling example: The Stasi officer, who Barbara supervises, is not inherently evil and nasty. He has also a very fragile side when we see him how desperately worried he is about his wife suffering of cancer.

Well, Barbara also shows a certain lack of emotions; a topic we find in all movies of Christian Petzold. But the audience notices all those feelings are boiling underneath the surface. He prefers to explore grey-areas or gaps in interpersonal relationships. Petzolds regular cinematographer Hans Fromm builds up the tension of genuine stolidity. The very authentically designed decors by K. D. Gruber add up to this.

The actors’ play is settled far away from overflowing emotions. Small gestures or facial expressions are enough to show the audience all the turmoil, the weighing up of what is the supposed »right« or »wrong.«

At least: Everything has just its two or more sides: people and situations, too. The question is what is worth to choose. And for that it takes courage. For me, Barbara was the best Competition entry at the Berlinale this year.

This review ha been published in KINO – German Film No. 103, p. 20.

Topics: Misc. | Comments Off on Barbara by Christian Petzold

Mitglieder stellen vor

By Dorothea Holloway | September 17, 2012

Die Veranstaltung der Akademie der Künste “Mitglieder stellen vor” kann nicht genug gelobt werden. Am 12. September stellte Jutta Brückner den Film “Liebe” von Michael Haneke vor.

Das Meisterwerk mit den wunderbaren Schauspielern Emmanuelle Riva, Isabelle Huppert und Jean-Louis Trintignant, in Cannes mit der Goldenen Palme geehrt, war in der Akademie am Hanseatenweg total ausverkauft und dem Publikum an diesem beeindruckenden Abend möchte ich auch eine Palme verleihen: Für Aufmerksamkeit, Ergriffenheit, Stille am Ende und dann herzlichen Beifall für Michael Haneke.

Informativ und heiter klang der Abend aus mit einem Gespräch zwischen Michael Haneke und dem Filmpublizisten Georg Seeßlen.

Topics: Film Reviews, Misc. | Comments Off on Mitglieder stellen vor

Hinterm Horizont, dann links

By F.-B. Habel | September 10, 2012

Längst war Bernd Böhlich, der in den achtziger Jahren an der HFF in Potsdam-Babelsberg sein Handwerk lernte, ein vielfach preisgekrönter Fernsehregisseur (u.a. mehrfach mit dem Adolf-Grimme-Preis ausgezeichnet), als er sich mit Ende vierzig den Wunsch erfüllte, Spielfilme zu inszenieren.

Die Sozialkomödie Du bist nicht allein (2007), stilistisch an Mike Leighs Filme, etwa Happy-Go-Lucky erinnernd, war sein bisher größter Kino-Erfolg. Neben den Hauptdarstellern Axel Prahl und Katharina Thalbach setzte er in Nebenrollen einstige Theater- und Fernsehlieblinge wie Walfriede Schmitt, Jürgen Holtz und Heinz Behrens ein. Bernd Böhlich liebt alte Komödianten. Schon als Regisseur im DDR-Fernsehen holte er verdiente Mimen wie Doris Thalmer, Lotte Meyer und Martin Hellberg für letzte Auftritte vor die Kamera. So nimmt es nicht wunder, dass er schon vor 11 Jahren ein Szenario über widerspenstige Alte im Heim (heute Senioren-Residenz genannt) geschrieben hat. Damals begann mit Lars Büchels Rentner-Komödie Jetzt oder nie, die den betagten Hauptdarstellerinnen den Ernst-Lubitsch-Preis einbrachte, der Boom der Filme, in denen rüstige Senioren noch einmal etwas Ungewöhnliches machen, weil sie mit ihrer Lebenssituation unzufrieden sind. Sicherlich liegt das Thema in der Luft, denn Menschen werden immer älter, während sich ihre soziale Situation oft verschlechtert. Daß die Rentner in Böhlichs Geschichte ein Flugzeug entführen, ließ aber Geldgeber – speziell nach 9/11 – zögern. Dürfte es nicht auch eine Straßenbahnentführung sein?

Inzwischen scheinen die Bedenken nicht mehr so stark zu sein, denn die Geschichte kam mit viel Augenzwinkern auf die Leinwand. Dabei ließ Böhlich in Hinterm Horizont, dann links nicht sein Anliegen aus den Augen. Wie gehen wir mit unseren Alten um? Schieben wir sie ab? Und wenn sie schon in ein Altersheim müssen, tun wir dann alles, was möglich ist, um ihnen das Leben so lebenswert wie möglich zu machen? Diese Polemik schob sich gelegentlich vor das komödiantische Spiel, für das er eine Garde großer alter Schauspieler aus Ost und West vor der Kamera versammelte.

Das Hauptpaar, das erst im Laufe der Handlung vorsichtig zueinander findet, bilden Otto Sander (West) und Angelica Domröse (Ostwest), die erst knapp über 70 sind, sich aber durchaus Altersbeschwerden anmerken lassen. Ihnen zur Seite bilden Monika Lennartz (Ost) und Herbert Feuerstein (West) ein Paar, bei dem der Mann die Frau stets unterdrückt, bis sie sich sachte emanzipiert. Die Publikumslieblinge Herbert Köfer (Ost) sowie Ralf Wolter und Tilo Prückner (beide West) sorgen für einige Gags, und die ehemalige Grand Dame der Ostberliner Volksbühne, Marion van de Kamp, spielt eine ehemalige Grand Dame der Volksbühne, wie man an den Postern in ihrem Zimmer deutlich sehen kann. Dass Böhlich ausgerechnet an ihre Figur die Erinnerung an Nazi-Minister Goebbels knüpft, wäre nicht nötig gewesen. Die jüngere Generation, darunter Anna Maria Mühe, Robert Stadlober und Steffi Kühnert, kann sich behaupten, ohne den Alten die Show zu stehlen.

Die etwas märchenhafte Komödie endet natürlich versöhnlich, aber die Denkanstöße, die sie gab, bleiben.

Topics: Film Reviews, German Film | Comments Off on Hinterm Horizont, dann links